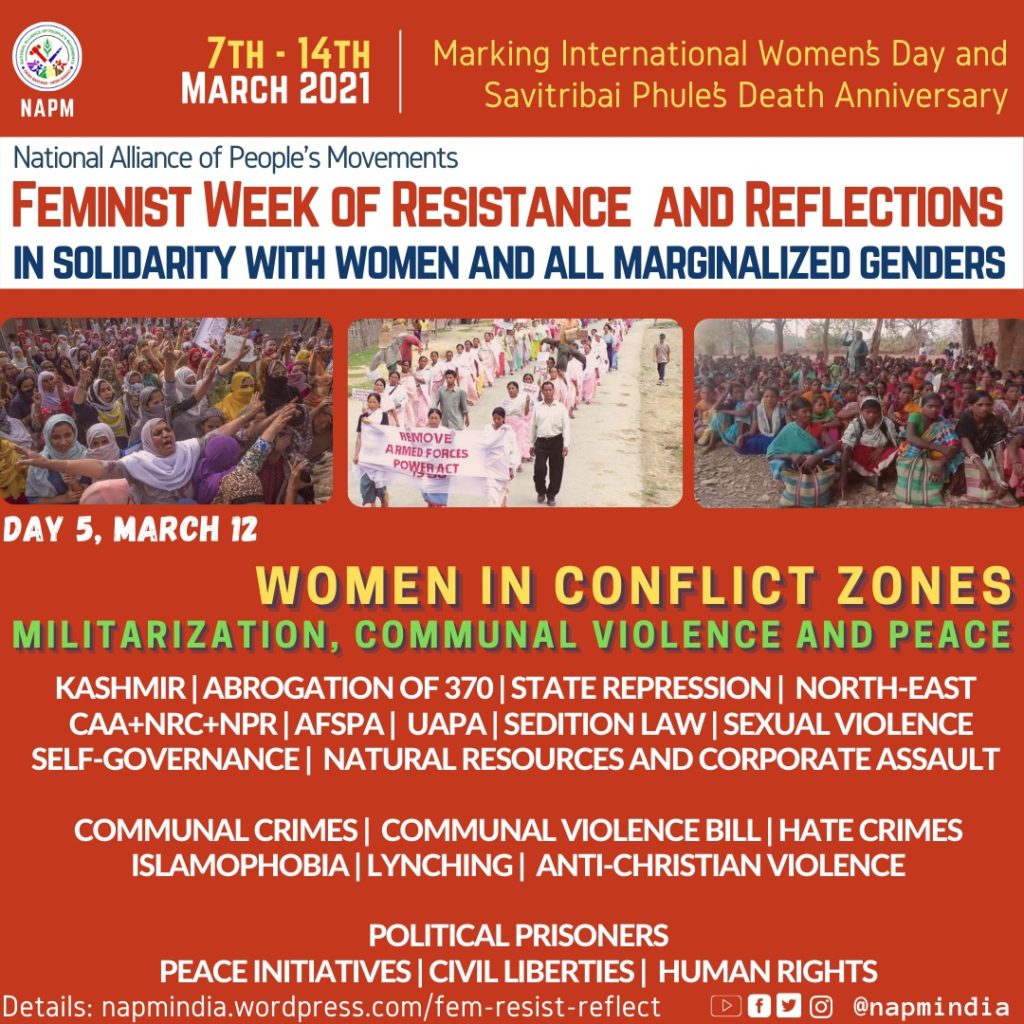

Militarization, Communal Violence and Peace

Marking International Women’s Day and Savitri Bai Phule’s Death Anniversary

Feminist Week of Resistance and Reflections (7th to 14th March)

12th March, 2021: Day 5 of the Feminist Week of Resistance and Reflections brings us to the geographically wide canvas on which is clearly marked the impact of militarization on the lives of people, especially women and gender non-conforming people from different conflict zones across the country. These need to be understood in the context of the rise of the Hindu-Nationalist ideology, intent on delivering the promised patriarchal masculinist state.

While neither communalization nor oppressive approaches of the State in certain parts of the country is new, the increase in number and intensity of state-sponsored crimes as well as the impunity with which they are carried out, draws into sharper focus the denial of agency of entire peoples asserting their rights to self-governance and political aspirations.

Women living in conflict zones and areas which have faced communal violence experience a very different level of gendered aggression at physical, psychological, socio-economic and sexual levels. Some of the key challenges they face include a perennial state of repression and combat, denial of agency and access to spaces of resistance; a denial of the right to self-determination and political assertion, physical and sexual violence, with no semblance of accountability and justice, deprivation of the right to be involved in developmental processes; all made more severe for women already marginalized on grounds of caste and class.

In the aforementioned context, today, we try at look at the experiences and resistances of women and gender non-conforming people in conflict areas such as:

Kashmir, North-Eastern region and adivasi areas of Central-Eastern India

- Areas affected by communal violence

- Draconian laws and political imprisonments

- Historical and contemporary questions around citizenship

A. CONFLICT ZONES

A.1 Kashmir

Despite the unique history of Kashmir’s accession to India, and Indian-oppression of Kashmiri people, the right-wing has always tried to project a counter and false narrative of ‘special treatment’ to Kashmir, citing Article 370 of the Constitution, thereby arousing resentment amongst sections of Indians. This reflected the Hindu rashtra’s intolerance to the possibility of self-determination and freedom, whether exercised by individuals or an entire region.

While Article 370 existed, it was used to justify growing militarization in the region, over decades, and undermine questions raised about the suffering within Kashmir. Within this, Kashmiri women bore the brunt of the physical destruction of homes, imprisonment, but also the consequences of mass enforced disappearances. Objectified by state, army and community in different ways, they continue to face overtly violent acts of rape and murder, over and above the dailiness of the trauma of ghost graves, of disrupted families, economic instability. They are forced to live in a state of constant fear and decreased access to most basic health and education, due to the permanent state of conflict.

The abrogation of Article 370 on 5th Aug, 2019 usurped not only the territory of Kashmir, but also the very idea of self-determination as a right within the Hindu Rashtra. Ever since, right-wing Indian men openly reduced Kashmiri women to their “physical” beauty, and imagined them as their ‘property’, denying the women any agency. The abrogation was ‘welcomed’ by almost all mega-corporates the very same day, who clearly were ‘looking forward’ to easy access to another territory to pillage, plunder and profit. All of this added on to the continuing militarization, state surveillance, political imprisonments under draconian laws like UAPA, PSA, AFSPA, clamp down on media, internet services and livelihoods of people in general.

There is a stark lack of legal action and justice in the horrendous gang rape at Kunan Poshpora, 30 years after the brutality took place. At the same time, ironically, 126 under-trial women are lingering in Kashmir’s prisons, in what amounts to punishment before affixing responsibility for their alleged crimes. The women of Kunan Poshpora refused to be silenced by attempts at shaming and cultural taboos. They have been campaigning relentlessly every year, demanding justice of the Indian state.

There is also a growing visibility of gender non-conforming people within Kashmir asserting individual identity as well as political aspirations, but the Indian state is denying both and claiming the abrogation of Article 370 is ‘in their interest’! Against numerous odds, Kashmiri women like Parveena Ahangar and persons of marginalized genders and sexualities have valiantly been part of the ongoing resistance against the excesses of the Indian State.

A.2 Struggles of Women in the North-East:

Just like Kashmir, many of the North-East areas have been subjected to militarization since Indian independence. With the impunity granted under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) and activists estimating that more than 1500 fake encounters took place in Manipur alone, women’s voices have been at the forefront of the fight against it. After a protracted struggle, the Supreme Court (2018) directed that FIRs against Sec 302 (murder) be filed against the police who were involved in the shooting. However, there has been little headway in this direction in the past 3 years.

Irom Sharmila’s sustained protest, through the 16 years of hunger strike, gave further visibility to the struggles of women against militarization and violence and the people’s movements against AFSPA, but also bore witness to the absolute unwillingness of the State to listen to the voices of the people, with AFSPA being invoked ruthlessly until today. The protests triggered by the rape and murder of Thangjam Manorama by the military forces brought out sharply women’s exhaustion with the imposed state of normalizing rape with impunity for the army.

Women face additional violence from the counter-militarization and underground movements which have emerged in response to the brutal state militarization of the area, the lack of recognition of autonomy and the exploitative relationship with mainland India vying for the resources of the North East. The formation of the Naga Mothers’ Association, for instance, working towards a decrease in violence between militant groups and the State, points sharply to the women caught in the ‘crossfire’, while at the same time refusing to give in to a peace that is anything less than the justice and freedom for which they have been fighting for decades.

Activists like Binalakshmi Nepram, leading ongoing work in supporting women survivors of sexual violence by the army, and advocating for disarmament and peace, have been articulating strongly the role that women, from their very specific locations in Manipur in particular and the North East in general, can play in the movement.

In the complex political context of the North-East, protests against the CAA-NRC have been significant since the bill was first introduced, leading to exemptions made due to the Inner Line Permit (IPL). While starting earlier, these protests received less visibility in mainland India, than the many Shaheenbaghs did, though the region continued to raise its voice against the communal implications of the legislation, with women very prominent in the struggle in Assam, Tripura, Nagaland. Along with the broader struggles that women have been part of in the region, to protect indigenous rights and resources, there have also been multiple attempts to raise complex questions of equity and gender justice within their communities, such as women’s right to property, fair participation in self-governance etc.

Added to the direct State violence against women and the impact of militarization, the attempt to exploit the rich natural resources through coal, uranium mining, mega hydro-electric projects have also taken a toll on the environment and health of people. These have been met with strong opposition by the communities and numerous activists like Agnes Kharshiing and Spelity Lyngdoh Langrin have borne the brunt of their vocal resistance.

A.3 Gender, Natural Resources and Corporate Assaults in Central-Eastern India

A similar plunder of natural resources has been taking place in Central India. Local people, mostly adivasis as well as left-wing groups have resisted the plunder, though invariably, all forms of resistance have been met with brutal clamp down by successive governments. Women have been at the forefront of the protests against numerous attempts to contravene the participatory framework drawn for Schedule V Areas by not taking local communities into confidence.

Be it the Niyamgiri movement in Odisha against Vedanta, the Pathalgadi self-rule movement in Jharkhand, the struggle of women in Bastar, Chhattisgarh, the resistance of adivasi women in Vakapalli, Andhra Pradesh against sexual violence by the ‘grey hounds’, the resistance of Gond and other adivasi women of Gadchiroli Maharashtra, adivasi women in the entire region, have over decades questioned and resisted the grossly unjust ‘developmental paradigm’ of the Indian Govt to exploit their natural resources through militarization, displacement, repression and sexual violence. The constant ‘conflict’ situation in these regions have made it even more difficult for women to access their rights under enabling legislations such as the Forests Rights Act, 2006; PESA Act, 1996 etc.

The interconnections between the State position enabling corporate greed at the expense of the lives, livelihoods, health and rights of adivasis in the area, and the militarization is at its clearest in Bastar, where it has led to brutal violence and arrests of activists raising their voices against it. The Gram Sabhas continue to be ignored and violated by the state machinery.

The normalization of sexual violence against women, in itself a way of causing terror among vulnerable communities, is apparent in multiple instances. In 2015 and 2016, Adivasi women in at least five villages of Chhattisgarh were sexually assaulted and raped by Chhattisgarh Police. After a report by activists was submitted to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), it urged the Chhattisgarh government to give monetary relief to the women, but no move was taken to prosecute the perpetrators.

Even after this, more reports of large-scale sexual violence came out of Bastar and Bijapur in March 2016. Documented cases of security forces stripping women naked and abusing them in different villages have to be seen not only as a mark of the normalization of violence by the state, and its consequent impunity, but also in relation to the constant attempt to separate people from their resource-rich lands. In this context, as in the context of communal violence, women’s bodies become an embodiment of the land where the battle is fought.

It is their resistance, as with the most visible cases of Soni Sori and Hidme Markam, that bothers the state most. They are targetted precisely because they are vocal about the ever-increasing para military camps, sexual and custodial violence against women, unjustifible incarceration of thousands of young adivasis and the denial of constitutionally granted rights for the marginalized people whose land and resources the state and corporates are trying to take over.

B. COMMUNAL VIOLENCE: FROM ENGINEERING TO LEGISLATING HATE

The ‘Rath Yatra’ leading to demolition of the Babri Masjid by Hindutva mobs in 1992 marked a new chapter in the communalization of the nation, with the right wing gaining more and more political power in the aftermath. Instead of fixing accountability for this crime, the targetting of muslim youth became a pattern ever since.

The State’s notorious communal agenda has become even more prominent after Gujarat 2002 set the blueprint for attempts to exterminate whole communities, with absolute impunity. Gujarat offered a ‘model’ in which the gruesome images of violence targeted specifically to Muslim women’s bodies, with a clear intention and understanding that these are a violation of a whole community, have caused trauma that is yet to heal. The socio-economic assaults on an already marginalized community both during the pogrom and at the ‘resettlement camps’ has left women in particular deeply scarred. Similar ghettoisation became part of the process of relief and rehabilitation in the state, and it continues until today, where in any case members of historically oppressed communities, Dalits, Muslims, Christians, are not accepted to live in dominant-community areas.

The orchestrated violence that the entire Muslim community suffered in 2002, for which accountability does not appear to be forthcoming, has in fact led to the strengthening of the image of hindutva political leadership through communal violence and islamophobia. The consequences of this continue to be seen today in multiple recent developments, which both rewrite the past and draw an even more violent blueprint for the future. Within this, is the complicated participation of certain women from the dominant, Hindu community, vocally encouraging rape and brutality on minority women. It took almost two decades for even the Supreme Court to marginally ‘compensate’ women like Bilkis who fought heroic battles against the violators.

Similar is the case of the 2013 Muzzafarnagar ‘riots’, where the affected and displaced communities, largely muslims, were reluctant to return to their villages while no action was taken against the accused. The situation here was compounded by the use of legal instruments in the form of affidavits, holding compensation hostage to signing undertakings that the Muslim people displaced by the violence would not return to their villages, thereby permanently changing the demographics of the area and agreeing to ghettoization. While repeating electoral benefits of this, the BJP in UP was also successful in converting the ‘riots’ into an exercise of land grab and economic impoverishment of the Muslim community.

Even as it acknowledged the criminal and unlawful nature of the Babri Masjid demolition, the Ayodhya judgement (2020) nearly legitimized the crime by not fixing any accountability and instead granting land for construction of the temple at the disputed site. While not very surprising, this unconstitutional verdict reaffirmed the second-class citizenship of Muslims at the hands of the Indian state and state institutions.

The most recent pogrom in Delhi last year (Feb-March, 2020) which took place amidst a vibrant movement led by women against the unjust law of citizenship of the BJP Govt (CAA) and a national project of communal disenfranchisement (NRC-NPR) is yet another striking example of perpetrators’ accountability not being fixed. Beyond the deaths and devastation of community life and property, there is a clear criminalization of muslims and women leading the Shaheenbagh protests, as well as others in solidarity including activists, academics and students who still linger in jails while those responsible for the Delhi ‘riots’ continue to be included in an expanded net of impunity. Absurdly, the positions of vitriolically violent figures like Pragya Thakur, Ragini Tiwari as well as Kapil Mishra-style calls for violence continue to receive state patronage.

In addition to these ‘larger instances’, the many other examples be ‘low – intensity’ communal violence, be it in Dhule, Maharashtra (Oct 2008 and Jan 2013) or even as recently as in Ujjain, Mandsaur, Indore in Madhya Pradesh (Jan-Feb, 2021) for collection of donations for the Ram Mandir, neither receive adequate attention nor is any accountability fixed, while women in particular are severely impacted. In fact, across all incidents of such violence, in addition to trauma, women bear the worst of the brunt of displacement and economic destitution in the aftermath.

The poverty and deprivation, lack of social security and the State refusing to address questions of jobs and livelihoods make basic safety and survival, primary concerns of the communities. Measures taken for immediate relief and then for rehabilitation in the case of mass communal violence often mean continued sexual violence against women. Together, the communal violence and its aftermath also make it possible for fear to further restrict the agency and mobility of women, as clearly seen in Muslim women’s (self)-employment trends even close on two decades after 2002, in Gujarat.

The engineering of the violence also pits Dalit-Bahujans against Muslims and Christians, furthering the brahminical agenda and unwittingly contributing to paving the way for the Hindu Rashtra promise held by the presence of Modi in Delhi, and CMs like Yogi Adityanath in UP. The increasing number of instances of lynching, targetting Muslim and Dalit people, as well as the ‘smaller’-scale instances of communal violence are indicative of a seeping of intolerance, and the certainty of not only impunity, but reward for horrifying violence against minority communities, into the consciousness of the ‘common person’.

Not only do the police and courts fail to address such violence, but there has also been a failure to provide a robust legal framework for instances of mass communal violence, and to address the way hate is engineered, in order to assign accountability, especially to political and administrative big-wigs, in spite of the discourse around the Communal Violence Bill taking off after the Gujarat Riots. The series of ‘anti-conversion’ ordinances in multiple states also bears testimony to the growing communalization of legislations.

C. DRACONIAN LAWS, POLITICAL IMPRISONMENTS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES

For several women across different locations, resistance in the face of state-sponsored violence and oppression is not simply a matter of dissent or differing with the hegemonic idea of the nation-state, it is a necessity for bare survival. It is the demand for husbands, brothers and sons to be returned home after enforced disappearances. It is the need to know if loved ones are dead or alive. It is to channelise the rage of seeing loved ones brutally raped or murdered by military forces. The only ‘sane response’ to seeing homes burned down, forests cut and rivers polluted. The very last resort for any hope of justice. And yet, when women resist this oppressive state machinery and its military, they are imprisoned under draconian laws such as UAPA, Sedition law and others.

Whether it is the most recent case of adivasi activist Hidme Markam in Chhattisgarh being arbitrarily picked up by the police from a protest, or the intimidation faced by Soni Soni over years or Kashmiri journalist Masharat Zahra, the state has used its machinery to prevent every possibility of the truth of this oppression from being spoken out, and any demands for justice to be made. Activists like Sudha Bhardwaj and Shoma Sen who have been human rights defenders for decades find themselves behind the bars for years, without access to bail, adequate healthcare or even visitation and communication with the outside world.

Even younger activists like Nodeep Kaur, Jyoti Jagtap, Gulfisha Fatima, Devangana Kalita, Ishrat Jehan, Safoora Zargar, Natasha Narwal, Disha Ravi, Nikita Jacob, and Amulya Leona and many others have been locked behind bars for fabricated offences. With the exception of the few of them who received bail, most remain incarcerated.

The experiences of these women vary even within the custodial and prison system, where they have to face humiliation, physical and mental torture and sexual violence at the hands of the authorities, at times being forced to give false statements to reproduce the police’s narrative of events, and facing constant intimidation and harassment. What remains a matter of some respite is the many forms of feminist resistance against these imprisonments and draconian laws, across the country.

D. GENDER AND CITIZENSHIP

At a very fundamental level, from the more obvious CAA-NPR-NRC, to each instance of communal violence, to the prioritization of corporate interest over the lives of marginalized communities, all of these are instances of a denial of basic citizenship rights, becoming more and more inscribed into legislative frameworks and entrenched in majoritarian cultural understanding and practice.

The CAA-NPR-NRC takes away the right to exist in a land, to earn, find shelter, find guaranteed protections by the state; to love and practice one’s own faith. The movement against the draconian CAA-NRC-NPR was primarily a feminist uprising. Projects such as the CAA-NRC, affect women, marginalized genders, who are further excluded from being able to ‘demonstrate’ citizenship. Poignant examples of this are already witnessed in Assam and some matters have been taken right upto the Apex Court, with little redress.

The protests in the many Shaheenbaghs were often framed in terms of an inclusive nation, respecting all communities and envisaging a future one wants to see for the younger generations, similar to the ongoing historic protests against the three anti-farmer acts.

Demands in instances of horrifying sexual violence by dominant communities, by the police and the military, are also framed in terms of human rights and citizenship rights which ought to be guaranteed; and so are, in fact, the demands for recognition of community agency in Schedule V and Schedule VI areas, but also in other instances of protests against the privatization and corporatization that deny already oppressed communities, particularly women, their equal belonging. Within these struggles, the specific ways in which trans* and gender-nonconforming persons are affected by such instances of violence fail to be taken into account, understood and addressed.

Through pulling together such threads during the Feminist Week of Resistance and Reflection, NAPM shall strive to support and amplify the many voices who from different locations have been continuously trying to stave off the realization of the military state, right-wing communal project. This would also in effect amount to a permanent disempowerment, deprivation of political and human rights, social security and constitutional guarantees for historically oppressed and marginalized communities.

We stand with those of us who are placed at particularly disadvantaged positions by intersecting axes of oppression, through caste, religion, gender, disability, ethnicity.

——————————

Should you wish to send us any feminist materials during this week from your struggles / organisations that you think needs to be amplified, please e-mail them to napmsocial@gmail.com or send them over whatsapp to 7618835699. Additionally, you can also tag us with these materials at our social media links on the scheduled date of each theme. Do follow https://napmindia.wordpress.

In solidarity,

National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM)

#FeministResistanceWeek: 7th to 14th March, 2021