Survivor Narratives in National Restoration: The Case of Vanni

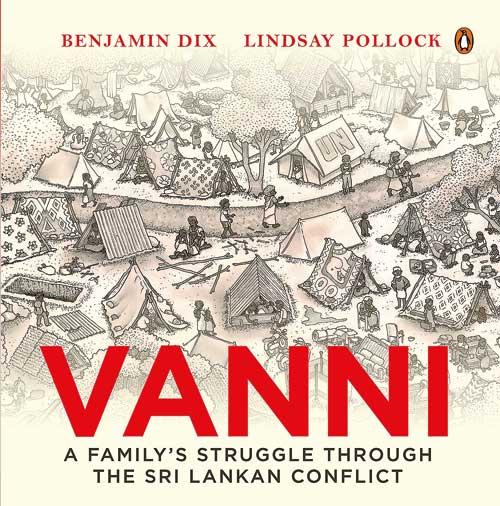

In 2019, Benjamin Dix and Lindsay Pollock produced the first graphic novel to emerge from Sri Lanka’s  civil war.

civil war.

The story is titled “Vanni: A Family’s Struggle through the Sri Lankan Conflict”, and is set between 2004 and 2009, from the Asian Tsunami to the war’s end when the state troops defeated the Liberation Tigers. Dix had been in Sri Lanka as an attaché of the United Nations before the UN was evacuated from Kilinochchi in 2008.

Drawing on his own empathy to events that followed, “Vanni” is set around a family and its neighbours, and their collective fate in a retreating human mass during the war’s closing months.

In the platform of literature emergent from the Sri Lankan civil war, “Vanni” breaks new ground. At one level, it contributes to the representation of the humanitarian crisis during the last months of conflict regarding which a debate still continues in human rights and diplomatic platforms. More significantly, “Vanni” makes its way to an elite canon of conflict-related graphic work in the league of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”, Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis”, Joe Sacco’s “Palestine”, and Deborah Ellis’ “The Breadwinner”.Dix and Pollock have managed to elevate a narrative of violence which, for over a decade, has received step-motherly treatment on its own shores and place it in an established discussion of bleak humanitarian tragedies of the modern world.

In Sri Lanka, survivor and witness narratives have emerged from each conflict the country has experienced. Predominantly in Sinhalese, the violence of 1971 and 1987-90 have produced an instructive body of such writing that offers a voice to victimization. Published predominantly in Tamil and – to a lesser degree – in English, survivor stories of the civil war is yet to become a public discourse among people who read only in Sinhalese. To this, there are exceptions like the autobiography of former Liberation Tigers political wing leader Subramaniam Sivakami alias Thamalini: her “Oru Koorvalin Nizhalil” (translated into Sinhalese by Saminathan Wimal) reached a wide audience in southern Sri Lanka. But, at crucial points of the story Thamalini consults an internal (or external) censor. It is indeed one kind of survivor story; but one that requires a reading between the lines.

are exceptions like the autobiography of former Liberation Tigers political wing leader Subramaniam Sivakami alias Thamalini: her “Oru Koorvalin Nizhalil” (translated into Sinhalese by Saminathan Wimal) reached a wide audience in southern Sri Lanka. But, at crucial points of the story Thamalini consults an internal (or external) censor. It is indeed one kind of survivor story; but one that requires a reading between the lines.

Focusing on incidents that took place in the last months of war, many witness accounts – both primary and secondary – have emerged since 2009. The question today is not of perpetration, but as to how we (as a people with a violent legacy) are ready to accept and be critical of these incidents. Publishing in English, journalists like Frances Harrison (“Still Counting the Dead”), Rohini Mohan (“The Season of Trouble”), Samanth Subramaniam (“This Divided Island”) and filmmakers such as Beate Arnestad (“Silenced Voices”) and Vishnu Vasu (“Butterfly”) have featured in their work survivor experiences. For instance, both Harrison and Arnestad spotlight the story of journalist A. Lokeesan who reported from within the war-zone until the very end. Others like N. Malathy – proficient in English to speak on her own – records in her memoir “A Fleeting Moment in My Country” a story that corroborates with other survivors.

“In the platform of literature emergent from Sri Lankan civil war, “Vanni” breaks new ground. At one level, it contributes to the representation of the humanitarian crisis during the last months of conflict regarding which a debate still continues in human rights and diplomatic platforms”

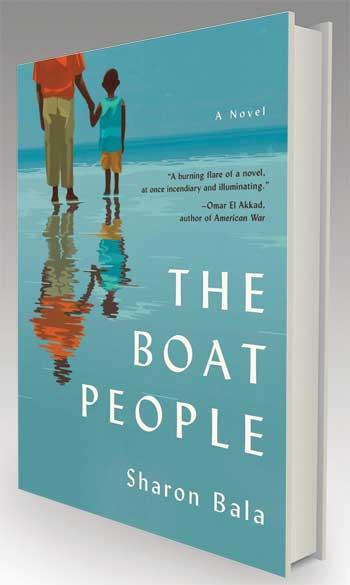

Over the past decade, creative writers have adopted the Vanni experience into their literary work with empathy. Shankari Chandran in “The Song of the Sun God” and Arun Arudpragasam in “The Story of a Brief Marriage”  represent this expanding category of which Sharon Bala’s “The Boat People” is a recent addition. “The Boat People” explores human smuggling after the war and the bitter fate of people like the main character Mahindan who, after a precarious sea journey, reached Canada to be detained. Writers like Para Paheer (Paheertharan Pararasasingam) document the fear that made people resort to daring sea journeys in a bid for a lifeline. In “The Power of Good People” Paheer writes of a generation that was born to a war in the 1980s,

represent this expanding category of which Sharon Bala’s “The Boat People” is a recent addition. “The Boat People” explores human smuggling after the war and the bitter fate of people like the main character Mahindan who, after a precarious sea journey, reached Canada to be detained. Writers like Para Paheer (Paheertharan Pararasasingam) document the fear that made people resort to daring sea journeys in a bid for a lifeline. In “The Power of Good People” Paheer writes of a generation that was born to a war in the 1980s,  and its long and harsh search for a place in society.

and its long and harsh search for a place in society.

Survivor narratives of the Vanni encourage us to look beyond sectarian politics and the simplistic notion of a war-victory with which politicians lull electorates to sleep. The survivor and witness narratives have in them the power to ready society for restoration, and to further the cause of justice. But, these narratives need to cross linguistic boundaries to arrive at the homes of the Sinhalese majority. They benefit from translation projects like what made available for the Sinhalese reader books like Sivarasa Karunaharan’s “MathakaVanniya”: a memory-driven elegy for the pre-war Vanni.Karunaharan’s informed nostalgia and powerful prose are retained in S. Wimal’s translation of the work. Once, S. Godage took a deep interest in translations between the two languages. “Ahasa Books” espoused the same cause in more recent years.

One day, the reading of conflict on an event-basis must end. Conflict should be read comparatively, and without the chip placed on your shoulder by your mythical ancestor. This is paramount for justice and social cohesion. Politics will relentlessly discourage it. But, for humanity, one must persist.

By :-

Vihanga Perera

(www.dailymirror.lk)